Today’s post is inspired by two news stories I’ve come across these last few days. One was a podcaster called Andrew Klavan claiming that women would always lose a swordfight against a man, if that man knew what he was doing. The other, a Kansas man requesting that the court grants him a motion to settle his divorce case through trial by combat! He claims that the practice is not explicitly banned in the United States of America or Kansas. I’m not going to comment on the legality of this proposal, but rather to take a look at the history of trial by combat and more specifically, their use to settle disputes between couples. And is the confidence of this man correct that the ex-wife stands no chance if it were to come to a duel?

Trial by combat has an ancient history, but it doesn’t appear to be something all cultures went for. Instead, it appears a practice restricted to Northern Europe. Neither Hammurabi’s legal code nor the Roman one had any provisions for judicial duels or the like. However, with the fall of the Roman Empire the practice spread to England, Gaul, and Italy.

The theory behind a trial by combat is that God (or gods) would favor the party that was in the right. But these duels or trials were not brawls. There were rules, restrictions, and laws that governed them. They could involve only two people or be fought by groups. They could be fought by those involved in the dispute or on behalf of them.

For example, Louis the Fair, son of Charlemagne, prescribed that trial by combat should be between witnesses of each side, rather than between the accuser and the accused. The Sachsenspiegel written in 1230 establishes that the parties must use shield and sword, may not wear anything but linen or leather, and neither may have the sun at their back.

Trial by combat wasn’t reserved solely for matters we would call a crime. They could be called to settle a dispute on land boundaries, it could be on a matter of honor, or about a debt. Hans Talhoffer, in his Thott codex from 1459, stated that seven offenses could elicit a judicial duel if there were no witnesses. These offenses were murder, treason, desertion, heresy, kidnapping, fraud or perjury, and rape.

Women were mostly excluded from trial by combat. However, we do have examples of judicial duels between spouses in the German-speaking countries and there were provisions for it in German law.

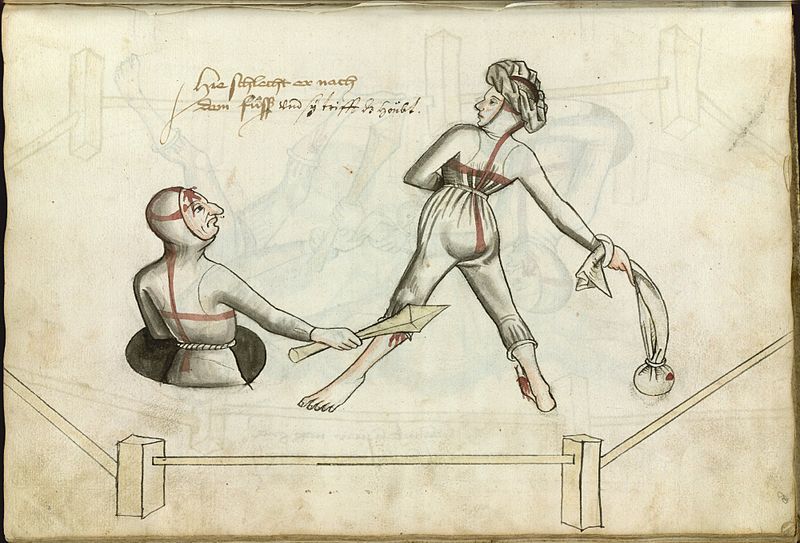

Both combatants were sown into these outfits to prevent them from hiding any illegal weapons or armor. The man was placed in a pit and got three wooden clubs. The woman received three rocks weighing somewhere between .5 and 2.5 kilograms. These rocks were wrapped in cloth.

The man was not allowed to leave the pit and would have to forfeit a club if he touched the edge of the pit with his hand or arm. If the woman struck him while he was handing over a club to the judge, she would have to surrender one of her stones.

The scene might look comedic, but it was deadly serious. We have it on record that in 1228, a woman killed a man in this manner in Berne, Switzerland. And even if the duel concluded with both parties alive, the loser would still die. The man would be executed, if the woman lost she would be buried alive.

However, there are other forms that a duel between a man and a woman can take. Paulus Kall, master of defense for the Duke of Bavaria said the following a manuscript in 1400:

The woman must be so prepared that a sleeve of her chemise extend a small ell beyond her hand like a little sack. There indeed is put a stone weighing three pounds; an dshe has nothing else but her chemise, and that is bound together between the legs with a lace. Then the man makes himself ready in the pit over against his wife. He is buried therein up to the girdle, and one hand is bound at the elbow to the side.

The accompanying illustration makes clear both parties are armed with a club.

However, another illustration from a different work shows a duel where both parties are partially undressed and face each other with short swords or daggers. Clearly, it wasn’t always thought that the woman needed an advantage to level the playing field.

But Allison Coudert, Professor of Religious Studies, makes the argument that these inclusions in works from the fourteenth and fifteenth century are anachronisms. The case in Berne I mentioned was one of the last on record where a couple engaged in this sort of duel.

Indeed, it became illegal in several places for a woman to strike her husband. The reverse, sadly, was not true. Even killing your wife was legal in certain areas, provided the man expressed remorse afterwards.

Which brings me to my final point. Spousal duels, strangely enough, were a sign of equality. As women’s legal position in society declined in the thirteenth century, they lost the ability to contest a matter by way of a judicial duel.

Bringing it back to current events, I don’t share the petitioner’s confidence he would win a trial by combat. If the judge allows it and goes by historic precedent, he would ensure that the duel was fair. Which would mean handicapping the man if he was stronger or more experienced.

But I don’t think we should bring them back. More than one person noted, even as far back as the eight century, that trial by combat didn’t produce justice. The strong won, the weak didn’t.

Sources:

Janin, Hunt (2009). Medieval Justice: Cases and Laws in France, England and Germany, 500-1500.

Medieval Misconceptions: TRIAL BY COMBAT, the Judicial Duel by Shadiversity